Lower Thames Crossing – Is this Tunnel a Bridge too Far?

The forthcoming examination of the revised National Highways proposals for a new downstream crossing of the Thames between Kent and Essex is likely to hear some very significant arguments about both the need for the major investment project, and the rationale behind its justification. They could also have an echo of the discussions on economic growth that have influenced the recent Conservative Party leadership elections. Here Phil Goodwin presents his analysis of the case expected to be tabled, and the wider issues it raises about scheme presentation, appraisal and political acceptability

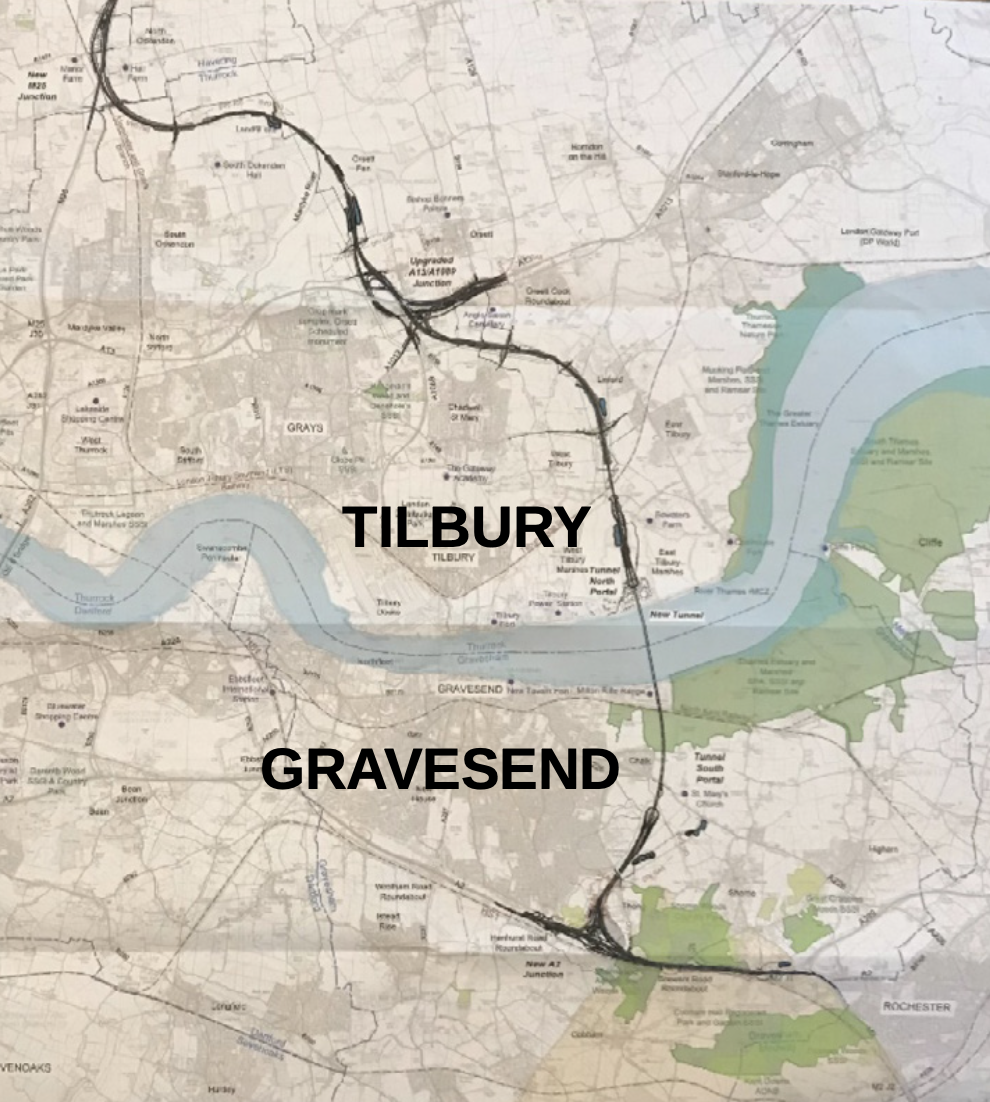

NATIONAL HIGHWAYS is about to submit for examination, within the planning process for Nationally Significant Infrastructure Projects, the largest road scheme in its current programme - the Lower Thames Crossing, from east of Gravesend on the south side of the river in Kent, to east of Tilbury on the north side in Essex.

Part of this submission, The Outline Business Case, is usually a key high-profile document, containing the most important summary of calculations of benefits and costs. Most surprisingly, NH has today refused to share this, or to consult on it in draft, on the grounds that it was currently incomplete - though it was evidently complete enough for NH to convince itself that the scheme was beneficial and robust, and submit it to Treasury.

As arguably the most directly affected local authority, Thurrock Council in Essex appealed to the Information Commissioner for its release. The commissioner last week ruled that

“The public interest favours disclosure because the project will have a major and lasting impact on people living and working in that area. Those people are entitled to take part in the associated decision- making and to be as fully informed as possible”.

On timing, the commissioner said that the Outline Business Case must be disclosed within 35 days or risk referral to the High Court, where it may be dealt with as contempt of court. National Highways has the right to Appeal within 28 days. This is a rare (and may be unprecedented) start to examination of a road project.

LTC was oddly absent from the Government’s recent list of road schemes to be accelerated as part of the then Prime Minister’s priority to ‘build more roads’. One unofficial suggestion was that the LTC’s unpublished economic rationale is so weak, and its cost so high, that it would be an eminent candidate for a cut or delay due to the financial stringency that is now universally expected. The cost was estimated at £8.2 billion back in March 2020, which had increased by around 20% from 2018. The word is that it now needs Treasury to again increase the budget, nearer to £10 billion. To put this into perspective, LTC would account for over a third of the total DfT Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020–2025 (RIS2) spending pot of £27.4 billion(1).

An obvious precedent to a government review of this expenditure would be the events nearly 30 years ago when Margaret Thatcher’s 1989 ‘Road to Prosperity’ roads programme was seriously cut back in 1994. This was also partly for reasons of financial pressure, but mainly due to a more fundamental change of transport planning perspective, initiated by public and professional opinion, and crystallised by a group of Conservative local authorities in the South-East of England. They demonstrated that the forecast traffic growth, assumed to underpin the motorway expansion, would then not actually fit into the congested local road space which could be made available in their areas. The logic of confronting this contradiction was later extended in John Prescott’s Transport White Paper under the subsequent Labour government, but it’s now often forgotten that the governmental change had been led by a new realism in Conservative local councils, taken up by a Conservative government.

Which brings me to the Conservative-run Thurrock Borough Council, who may now turn out to be the new David challenging National Highways’ Goliath. Their newly launched website(2), under the stark headline ‘Why we oppose the Lower Thames Crossing’, points out that LTC is in effect the creation of a new M25 outer-orbital route, far greater in scale than other in-line increases in road capacity. It would generate a great increase in traffic, is based on inadequate consultation, and would take almost 10% of the Borough’s land area, including a substantial swathe of green belt land.

I’ve had the privilege in recent months of working with Thurrock Council, who field an impressive technical and professional team which any local authority would be pleased to employ. This column summarises some of the work that has been undertaken as part of their engagement with NH and in the public domain. To this I add my own observations, which should not be taken as representing the views of the Council.

Thurrock is a Unitary Authority with Borough status, in the County of Essex, immediately on the North bank of the Thames, and bordering the London Borough of Havering. It has a population of 175,000 and a mix of serious industry (including two significant ports, Tilbury and DP World), low lying marshes, Green Belt, urban development and semi-rural villages. It has eight railway stations, providing local connections in Essex and several routes into London. There was a serious flood in 1953, and smaller ones since. It is a hardworking, but not wealthy area – a candidate for ‘levelling up’ rather than a rich suburban feeder to London.

The Lower Thames Crossing is the latest version of a major proposed road crossing of the Thames further down river than any other, and several miles east of the Dartford Tunnel and Queen Elizabeth II bridge carrying the M25. This additional cross river link has, in one form or another, been on the books of National Highways and its predecessors (Highways England, Highways Agency, Ministry of Transport) for decades. It is currently by far the biggest project in the controversial national road programme and like others will undoubtedly be subject to objections, opposition and legal challenge. A previous submission in October 2020 was withdrawn by NH - they had considered their proposal was ready to go, but shortly before the planned submission the Planning Inspectorate for England (PINS) noted that the consultation had not been adequate under the terms of the Planning Act 2008.

Since then, local authorities have engaged in many meetings with National Highways, but with some very strange features, one of which was a very tight restriction over use of modelling and forecasting information. Local authorities were provided with NH cordon models for their own area, but only on strict condition that they did not try to collate or share this information in discussion with neighbouring authorities or anybody else. Likewise, major stakeholders have also had to sign up to strict conditions not to share information that NH has shown them. So, nobody – apart from NH itself – has been able to understand the overall traffic patterns on which NH has based its appraisal, or allowed access to NH’s strategic traffic model, developed entirely with public funds, to run tests or variants.

There are two problematic matters of concern about the LTC proposition to come out of the consultation on it that merit some discussion. First, despite the planning process for NSIPs being designed as a front-loaded process where engagement is supposed to lead to resolution of issues between stakeholders before examination, at the latest count there are some 300 issues of disagreement between Thurrock and NH. Many of these will have to be reported as ‘not agreed’ to the Planning Inspectorate, in a ‘Statement of (un) Common Ground’. Second, the basic design, project formulation, traffic forecasts and appraisal were done before Covid, before Brexit, before publication of the Government’s transport decarbonisation strategy, and before the current energy crisis. In turn, that means there has been no consideration of the implications of recent Government recasting of UK economic prospects, which now expect years of pressure: rising price levels, restrictions on spending, pressure on real incomes and employment. This uncomfortable prospect is profoundly different from the steady economic assumptions which NH used to forecast traffic growth and congestion for LTC.

Issues of disagreement between Thurrock and National Highways

I can’t here list all of the areas of disagreement between Thurrock and National Highways over the merit and detailed technical operations of the scheme, but in summary the most important seem to me to include the following:

Thurrock, as the ‘host’ of one side of the proposed tunnel (Gravesend is the corresponding area in Kent on the other side of the river) carries the burden of most of the supporting changes to infrastructure, with serious impact on its own plans and potential development, as well as the brunt of local noise and emissions, and five years or more of the traffic disruption during construction. It expects to receive very little local actual direct benefit from the tunnel, by comparison with its cost and damage.

In the immediate vicinity of the major works, there would be significant long term consequences requiring expansion or realignment of local roads, junctions and links, which have been rather dismissed by National Highways and with inadequate provision for remedy. The detailed local modelling shows different effects on queuing and capacity from the strategic modelling, and neither takes full account of local growth of housing and Freeports, both central planks of different government departments. The Borough is likely to resent the implication that it is their job to provide additional local road capacity, and remedial traffic management, only made necessary as a result of a scheme they currently don’t support.

The Borough has – in accordance with Government policy – intentions to improve provision for walking, cycling and public transport, as well as improvements to the public realm, in support of proposals for housing and employment growth. National Highways refuse to take these into account, giving as the reason that future transport plans are not sufficiently clearly defined and securely funded (though this condition has not consistently been applied to other uncertain elements in the traffic projections). This raises much bigger questions of alternatives mentioned below.

The supposed traffic and economic benefits, as far as they can currently be judged, seem doubtful. One of the objectives, congestion relief to the Dartford Bridge, seems to be small and short lived. The Ports are interested in enhanced capacity for freight, but their markets are mainly between Europe and the Midlands and North of England, and not substantially reliant on a new tunnel going South.

The wider claims of economic benefit are obviously crucial to any case for the scheme, and the Examination will need to investigate this at local, regional and national level, in accordance with procedural requirements. Thurrock Council has repeatedly asked both NH and the Treasury for details of demonstrable economic benefit, but has been repeatedly refused, despite FOI requests usually unnecessary between public sector bodies. It is difficult to see how examination of the scheme can sensibly proceed until the basic business case, and its underlying analysis, are open to scrutiny.

These local concerns are part of a much bigger set of problems, which lie at the heart of the running flaws and unresolved tensions in the road and environmental strategies for England as a whole. They include the treatment of alternatives, traffic forecasts, and certain key environmental impacts.

Alternatives

A key feature of any appraisal system is that (at best) it is only as good as the alternatives that are being judged. This is embedded in the general principles of the official DfT Transport Appraisal Guidelines (TAG) and indeed is a common property of rigorous appraisal generally. For road appraisal the general approach is that alternatives should not be confined to detailed alignments, but should also include modal alternatives, public transport and active travel, and may also include demand management alternatives, such as speed control, reallocation of road space, land use change, management changes to produce different patterns of origins and destinations, or different ways of organising the activities which travel is for (e.g. telecommunications, working from home, etc). These alternatives typically provide significantly better measures of value for money than expanding road capacity, better environmental and health impacts, and more efficient uses of resources. Pricing and taxation assumptions are crucial, and will become more so in the context of financial constraints. The prospects for motoring costs, both for electric and fossil fuel vehicles, obviously affect traffic forecasts as well as Government revenue.

However, in this case there has been no more than cursory consideration of modal and other alternatives, in the most general, non-specific terms, and so long ago that the radical changes brought about by Covid, Brexit, climate targets, and the current economic situation were unthinkable. Therefore, alternatives now become relevant even if they had not been previously.

Despite the fact that LTC is in the current Road Investment Strategy (RIS), it cannot be in the public interest to proceed with a scheme of this size as if the original circumstances still apply without reassessing the case for alternatives. There are mechanisms for updating the RIS when circumstances and/or policy have changed: in my opinion that bar is met. A serious look at alternatives, especially modal alternatives, should be considered as necessary preparation before a scheme is ready for submission. One of the responsibilities of the Examining Authority is to satisfy itself that this consideration of alternatives has been done (as provided for in the DfT’s 2014 National Policy Statement for National Networks(4) which itself specifies that the latest ‘successor documents’ should be used).

There has been no more than cursory consideration of modal and other alternatives, in the most general, non-specific terms, and so long ago that the radical changes brought about by Covid, Brexit, climate targets, and the current economic situation were unthinkable.

An important factor here has been the rapid recent transformation of transport and employment in the Thames Gateway area to the East of London, as Canary Wharf already showed, and the completion of the Elizabeth Line from Abbey Wood and Shenfield now further facilitates. There are already two separate serious proposals for extending that new cross-London regional rail link further into Kent or Essex or both. There is much scope for expansion of priority bus services alongside this, with the example of the Fastrack Arriva Bus Rapid Transit routes that combine high quality buses with a frequent service, linking Dartford, Bluewater and Gravesend. Measures used to allow buses to avoid traffic include signal priority, reserved lanes, and dedicated busways. A very recent development is the decision of Eurostar to reduce its service level and intermediate stops at Ebbsfleet and Ashford in the light of Covid-related impacts on travel and Brexit-related administrative changes. This suggests to me that there is new potential for using the spare capacity on Eurostar’s fast rail tunnel to expand local rail services using that tunnel (e.g. with a new station near the Dartford Tunnel where railway lines converge, and would connect to both Grays and Ebbsfleet, linking the extensive existing rail networks in Essex and Kent. There are also the further developing Thames Clipper ‘Uber Boat’ river services for commuting and leisure to consider, recently extending Eastwards, from Woolwich to the new Tube station at Barking Riverside and being used informally for multiple one-stop river ferry crossings. Global private markets investment firm Northleaf Capital Partners promised new investment to support Uber Boat by Thames Clippers’ ambitious growth plans and greater economic development on and around the River Thames when acquiring a majority interest in the former AEG-owned business earlier this year(5).

Any or all of these developments can change the options for some of the traffic predicted to use the LTC. Thus they have a significance both as alternatives in their own right, and also as scenarios changing the amount of traffic forecast to be using the Tunnel, and therefore its value for money.

Overall Traffic Forecasts

The way in which transport project appraisal is done – especially in cases where the promoter has a strong presumption in favour of a positive result – involves a sort of ‘sweet spot’ in traffic forecasts. If forecast traffic is too high, then the scheme will fail because there is no way of delivering enough capacity to meet them. If forecast traffic is too low, the scheme will fail because there are not enough potential large time savings from relief of congestion. Something like a steady assumed increase in traffic volume over the appraisal period of around 30% to 40% sometimes gives the desired result. This was a feature of the previous forecasts and – it seems – the current ones.

But that projection is very odd, when you think of how much has changed in that last few years – more, probably, than any time in current professional lifetimes – and how much more is expected to change in the next 30 to 50 years. At the national level, every ‘central’ long term road traffic forecast since 1989 has overestimated growth, and has had to be revised downwards as has been recorded in my own columns in LTT over the years, and in DfT’s periodic National Road Traffic Forecast revisions (soon to become National Road Traffic Projections, in seeming recognition of that fact). And while the accuracy of traffic forecasts of particular schemes have ranged very widely, with both large overestimates and underestimates, there has been a distinct tendency to overestimate the forecasts for the ‘without’ case used as a baseline (offset by a tendency to underestimate the induced traffic). Taken together, this has significantly overestimated the value for money on which the business cases are built in many schemes, therefore the question of how much the (still unpublished) business case depends on unrealistically high general traffic growth now looks to be crucial.

So, in the forthcoming DCO examination, (if the application is accepted by the Planning Inspectorate), there should be exceptionally close scrutiny of three critical quantities:

-

the assumed ‘base’ or ‘do-nothing’ trend of traffic without the tunnel;

-

the forecast traffic trends ‘with’ the tunnel; and

-

the range of realistic contingencies or scenarios for testing risk factors.

Despite the temptation to view such technical issues as peripheral, they should be informing the direction of national roads policy, and be particularly critical to decision making about this, the most costly road project in the country. Since 2015 the DfT has accepted a wider range of possible realistic scenarios than has ever been included in NH projections. They should not be glossed over.

Environmental Implications

There are many important environmental aspects of the scheme. I’d mention two specific aspects, flooding, and climate.

Risk of Flooding

River valleys are of course especially vulnerable to flooding, especially in low-lying, rather flat land as applies here. There had been good work on flood defences, and in the last review the area was not designated as high short-term risk. But it is now clear that there is a much more substantial medium and long term serious risk. Officially, the plans for a major additional lower Thames flood barrier are due to be firmed up by 2025(6). The original plan in 2012 thought that expenditure of £3.3 billion until 2050 and up to £8 billion in the second half of the century would be sufficient to improve and upgrade the flood defence system, but this did not take into account an increase of the risk levels in 2018 or the DEFRA recommendations last year that 2°C or 4°C increase in global temperature should be allowed for as contingencies for project appraisal. These would show the whole Thames Valley at serious risk of flooding.

Therefore, it must be assumed that the planned 2025 flood report is highly likely – one might say certain – to very substantially increase the risk levels and the necessary expenditure, and to accelerate the time span. On current timetables, the inquiry into LTC would take place without recognition of the parallel transformational work on the whole context of flood risk along the Thames or the detail of where and how this would be tackled. This seems very unfortunate timing.

There must be some doubt about whether it is wise to dig expensive tunnels in an area at risk of flooding. when climate change is already irreversibly increasing sea levels and especially exacerbated if global climate commitments are not met.

Carbon Emissions

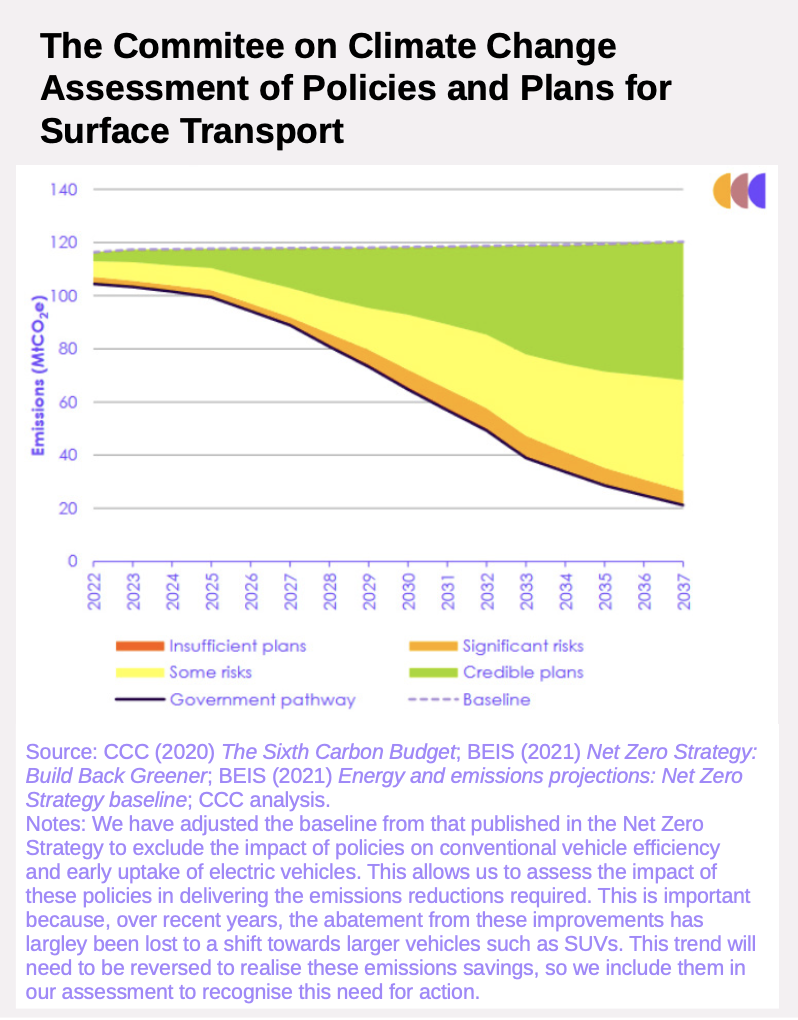

In their recent road appraisals National Highways has asserted that the carbon emissions resulting from their projects are so small that they can be treated as irrelevant (‘de minimis’ in legal terms), and argued that the assumed success of the transport carbon strategy generally means that there will be even less carbon emissions than had previously been feared. This scheme, however, because of its size and its provision of a major new link, is probably going to be the biggest potential generator of increased carbon emissions in the whole programme. The Climate Change Commission recently reported(7) (my italics)

-

‘The TDP and Net Zero Strategy represented a big step forward in recognising the need to reduce traffic growth’...

-

‘...Substantial investment in roadbuilding should only proceed if it can be justified how it fits within a broader suite of policies that are compatible with the UK’s Net Zero trajectory. Both the Scottish and Welsh Governments have recently committed to no longer invest in road-building to cater for unconstrained increases in traffic volumes’

The CCC showed that the current trajectory is not compatible with the 2050 net zero target or the shorter-term targets that would be implied in the coming 5 and 10 years.

The DfT itself also agrees that the current transport trajectory is not compliant with net zero targets(8). Close reading of the DfT’s own decarbonisation strategy strongly implies that they are (very sensibly) calculating a significant traffic reduction to close the gap. They are not yet releasing the detailed figures on how much, and a Freedom of Information case(9) is being pursued by Professor Marsden of Leeds University for the DfT to release the national traffic forecasts which underpin the Decarbonisation Strategy. Meanwhile it seems certain that the traffic projections required for net zero will not show the scale of traffic growth which is critical in National Highways’ case for LTC.

The ‘sweet spot’ traffic forecasts do not allow for risk factors in either the failure or the success of climate policy: either the radical and unpleasant transformation of economic geography that would follow from continuing global warming, or the significantly lower traffic levels that would be involved in successful decarbonisation. In both cases, treatment of alternative scenarios is at the heart of the credibility of the project appraisal(10).

For all these reasons, I’m expecting, therefore, that there will be a strong and critical challenge to the scheme at any forthcoming Examination, not only from the local residents and campaigners, and their professional and technical supporters, but also from, at least, the most affected local authority.

It is usual for such submissions to be accompanied by a very large amount of material, written by NH and its consultants, claiming to justify the LTC proposal. It will be published soon on the PINS website. It will be deserving of most careful attention.

I hope that this column may help in that process, and in putting a spotlight on what I believe to be some very important and sensitive issues in the technical appendices and their annexes and footnotes at this watershed moment for the East Thames corridor itself, and for the way we should now consider all such major road schemes. Watch this space.

References:

-

Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020-2025 (https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/ attachment_data/file/951100/road-investment-strategy-2-2020-2025.pdf)

-

Its progress may be followed at https://www.whatdotheyknow.com/request/traffic_level_and_electric_vehic

-

Anable & Goodwin (2022) https://elements.lttmagazine.co.uk/p/LTT829.pdf#page=19

Further contributions on the issues raised are welcome. Please send to hello@lttmagazine.co.uk

Phil Goodwin is Emeritus Professor of Transport Policy at UCL and UWE, and Senior Fellow of the Foundation for Integrated Transport.

Email: philinelh@yahoo.com

(c) 2022 LTT Magazine and lttmagazine.co.uk