Twenty years on - how does that letter the 28 professors sent to Transport Secretary Alastair Darling look now?

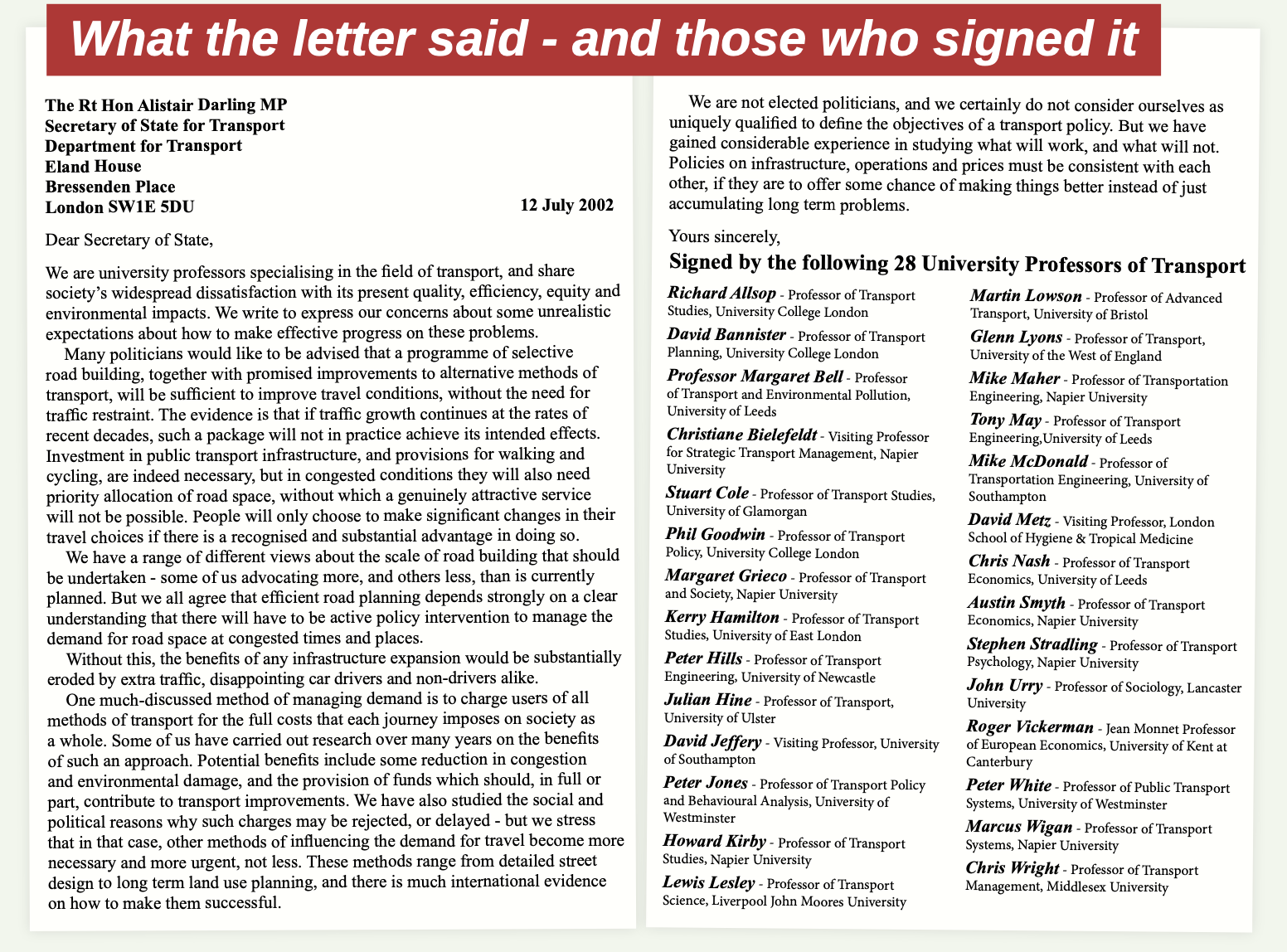

IT WAS 20 YEARS AGO this month that 28 of the UK’s Transport Professors wrote to the then Secretary of State for Transport Alastair Darling, expressing their concern about the government’s transport policy at the time.

The letter was initiated by Professor Phil Goodwin and sent by the Transport Planning Society chair, Professor Glenn Lyons.

Perhaps what is most significant about this anniversary is to note what it was that the professors were concerned about and proposing ways to address, and to compare that with today’s hot topics on the transport agenda.

What they said in that letter majored on a call for active policy intervention to manage the demand for road space at congested times and places by charging users of all methods of transport for the full costs that each journey imposes on society as a whole. Whilst this was broadly addressing the environmental impact of transport it was not overtly expressing any particular concern about global warming, climate change and the need for decarbonisation - and certainly not a quest to achieve net zero.

Two other significant points must be the tone of the letter and the role the professors sought to play, and the characteristics of the group of signatories that was brought together to that end.

As to the tone, it was quite self effacing and relatively benign. “We are not elected politicians, and we certainly do not consider ourselves as uniquely qualified to define the objectives of a transport policy” they said. “But we have gained considerable experience in studying what will work, and what will not. Policies on infrastructure, operations and prices must be consistent with each other, if they are to offer some chance of making things better instead of just accumulating long term problems.”

Regarding the signatories, it was something of a motley band, including seven professors from Napier University, three each from University College London and University of Leeds, two each from Southampton University and University of Westminster and 11 from other institutions in the country. It must have been an interesting task to identify the potential persons to approach, and indeed to know if anyone who was asked chose to decline.

Lead author Phil Goodwin recalls “The letter was quite long, and very carefully drafted. The key text in securing agreement on the essential point while avoiding endless redrafts, was ‘We have a range of different views about the scale of road building that should be undertaken... But we all agree that...there will have to be active policy intervention to manage the demand for road space at congested times and places. Without this, the benefits of any infrastructure expansion would be substantially eroded by extra traffic, disappointing car drivers and non-drivers alike’.”

The key text in securing agreement on the essential point was ‘We all agree that... there will have to be active policy intervention to manage the demand for road space at congested times and places.

Phil Goodwin, Emeritus Professor of Transport Policy at UCL and UWE, and Senior Fellow of the Foundation for Integrated Transport.

Whilst not all of the potential cast of professors involved in transport at the time were signatories, the 28 that were, were seen as a significant group of the most senior and erudite thinkers on transport.

There was even comment, embodied in a LTT cartoon at the time, about just how many transport professors there were, given that only a few years earlier, it would have been difficult to find more than a dozen.

Research by LTT for this article has identified that there now are well over 130 professors either featuring the word transport in their title, or self evidently being substantially involved in transport matters, embraced in significant range of perspectives from engineering, safety, sustainability, psychology, human factors, rail technology, air transport, tourism, travel behaviour, economics and finance, urban resilience and modelling — a much broader range of disciplines than those that made up the 28 signatories to the 2002 letter. Their departments are also much more varied - Active Travel Academy at University of Westminster, Department of Architecture at Cambridge University, Future Mobility Research Group at University of Newcastle, School of Creative and Cultural Business at Robert Gordon University, for example.

Indeed it is arguable that any proposition in a letter being suggested today might not find favour across all this elite academic population. Another fascinating fact is that of the 28 original signatories, only four were female, whereas in the new LTT list the proportion is one third (excluding Emeritus, Visiting and Honorary Professors). Indeed the first female professor of transport is said to have been Kerry Hamilton, was only appointed in 1997 at the University of East London.

Two of the other interesting aspects of the letter are that it provided some exposure to the Transport Planning Society, then only five years old, and also was first proposed in a column written for LTT by Phil Goodwin — the beginnings of a regular contribution from him that has continued ever since.

Other period pieces to be observed are the structure of transport responsibilities within government, which had only just moved away from the era of the mega Department of Environment Transport, Local Government and the Regions (DTLR) begun under Deputy Prime Minister, John Prescott, and finally dissolved after Stephen Byers resigned under a cloud as Secretary of State, to being a more conventional transport ministerial portfolio as taken up by Alastair Darling earlier that year.

Seeing the letter in its particular time slot, Goodwin thinks things have changed a lot in the two decades that followed. “The political context now is very different, dominated by the three policy crises of Covid, Brexit and Climate Change, and the governance crisis in public standards and practices” he says. “Could a polite intervention by academics have a useful impact now? I would say that the same core text still applies, even more strongly. A contemporary translation would be something like “we have a range of different views about transport policy, but we agree that neither congestion nor climate can be solved without active intervention to reduce the volume of traffic”.

“My sense is that something over 80% of the 100+ current transport professors might agree with that, though with more nervousness about signing.”

Glenn Lyons agrees that the world has most definitely moved on.

“Twenty years ago it seemed that this was a rather novel course of collective action to call for change”, he says. “Sadly, fast- forward to the present and I think the sort of collective action needed is in a different league altogether. Time was on our side two decades ago, but there is an unnerving urgency now to the need for fundamental changes to our transport system and how it is used – if we remain committed to achieving a decarbonised economy. Collective action is manifest in the form of public protest in the face of inertia, but we also require collective action among stakeholders responsible for transport supply and among consumers in terms of transport system use.”

What would be the equivalent now? Is there a consensus on the key message from the leading transport thinkers? Is that the right definition of whose voices should be heard anyway? What media would be used to get the message across now? Would it be a letter, a petition, a vigil, a protest march, a boycott, an online campaign, a barrage of social media messaging?

How complex and how carefully crafted would be the proposition? Or would it just be a 280 character twitter statement effectively saying ‘JFDI’ or some kind of campaign slogan rather than a nuanced policy discussion.

Certainly 20 years ago the world of transport, transport professors and society more generally were rather different from today. And the questions remain- did that letter make any difference to policy then, and what would make any difference today?

(c) 2022 LTT Magazine and lttmagazine.co.uk